October is here, and the dropping temperatures have raised my excitement for excellent fall photography opportunities. Autumn is my favorite photographic season, and this post will focus in on one quick photography tool that will rapidly improve your autumn images: the circular polarizer.

A circular polarizer is a filter that attaches to the front of your lens. Rotating the filter changes which wavelengths of light are visible through the filter. This effect can serve to emphasize the blue in blue skies and cut down or eliminate reflections in water. A polarizer can really make the colors of fall leaves pop and brighten up a bright blue background for them too.

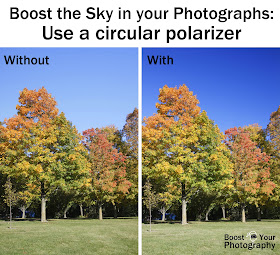

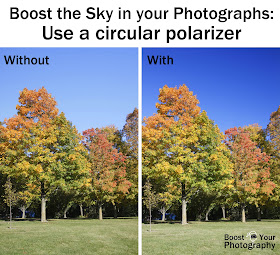

These two images demonstrate how a polarizing filter can improve an image. The image on the left was shot at f/5, 1/50th of a second, while the image on the left was shot at f/4.5, 1/40th of a second. Both images were taken with the polarizing filter attached to the camera, but the filter was rotated in between images to first minimize and then maximize the polarizing effect. The impact of the circular polarizer can be seen most clearly in the brightening of the sky and in the increased saturation of the colors in the right-hand image.

|

| Example of a circular polarizer. The shadow is created by the light-blocking effect of the polarizer. |

Tips for Using a Circular Polarizer

First off, a circular polarizer has two elements. The back of the filter contains the threads that allow you to screw it on and attach it to the front of your lens. The front of the filter rotates freely around, allowing you to align and adjust the filter for the look you want. (Some filters, like the

Cokin series, have a special holder that then attaches to the lens, but using and rotating the filter works in the same way as described below.) If you use a UV filter on your lens at all times for protection (and you should), then you need to remove the UV filter before attaching the circular polarizer, otherwise you may have an unwanted vignette effect where the circular edges of the polarizer may become visible in the corners of your images, as in the image below.

|

| I screwed multiple filters onto the front of my lens when taking this image. As a result, the edges of the filters are visible, created an unwanted vignette effect. |

Here’s what no book ever came out and told me about circular polarizers: there is no 'correct' way to align a polarizer. The first several times I went out and used my first polarizer, I was continually frustrated because I could not find any markings to indicate a 'maximum' or 'minimum' polarizing alignment. I would look through the viewfinder, spin the polarizer around, and see nothing happening. I would try taking a picture, rotating the polarizer 90 degrees, take another picture, rotate, etc. and notice no apparent differences between the images. I finally went so far as to mark the 'top' of the filter edge with white out, so that I could at least see where I was adjusting it to and from.

I thought I was crazy. I had been reading all about photographers raving about their polarizers, and nothing happened that I could see when I was using it … until I happened to aim at some windows.

|

| Changing window visibility with a circular polarizer |

The windows of the Red Cross building finally showed me the impact of what the polarizer could do. At one alignment (left), I could see the light shining through the windows and into the rooms within, but when I began to rotate the polarizer (right), I could see the windows become opaque and then nearly completely solid. At the time, I did not notice the changing blue hues in the sky, but they were more obvious to me when viewing the photographs on my computer.

This changing visibility through the windows is the same effect that polarizers have when you are using them to shoot water. At one alignment, the polarizer will be letting in the light going through the water and show you what is underneath, while at another alignment, you will only see the light bouncing off the water and not be able to see underneath. Photographers exploit this tendency of polarizers when shooting water to minimize the glare or reflections of bouncing light in the image.

After further experimentation and reading, I finally understood that a polarizer works best in specific situations. To start, a polarizing filter really works when the sun is at a 90 degree angle to your subject (as in, the sun should be shining off to one of your shoulders). The effect is greatly diminished if you are facing directly towards or away from the sun or if the sun is directly overhead. Depending on the relative angle of the sun and your subject, you may find that the polarizer creates more of a gradient than an even color tone across the sky.

|

| Incorrect use of a polarizer can result in a drastic change in color and darkness across the sky. |

Once you have found a scene that will utilize the effects of the polarizer, you should be able to see the changes happening as you rotate the filter. The blue of the sky is a good place to watch. As you rotate, you will notice subtle changes in the blue from a deeper, darker color to a softer, lighter color and back. It is those deep, dark blues that make the circular polarizer popular, but you may choose an in-between version, if it better fits your vision. This is where there is no 'correct' answer. The exact angle at which you align the polarizer for the effect you want depends on many factors including the angle of the sun in the sky, the angle of the sun relative to the camera, and the angles at which light is bouncing off your subject and into your camera. So there is no automatic 'maximum polarization' setting. If someone had only told me that upfront, I would have felt far less foolish …

Another thing to keep in mind is that the using a polarizer will also change the settings that you need to use for that particular situation. A polarizer, by definition, blocks out certain types of light, so when using a polarizer, you will need to use a wider aperture or a longer shutter speed to accommodate for that loss of light and ensure a properly exposed image.

|

| Comparison of the impact of a circular polarizer on the sky and autumn leaves. |

As an example, if you first composed a scene using aperture priority set at f/8 (for a reasonable depth of field but still a quick shutter), then the camera might suggest a shutter speed of 1/100th of a second. If you then attached a circular polarizer to your lens and spun it to maximize the polarizing effect, then your camera, still set for f/8, might now suggest a shutter speed of 1/50 of a second. (For the technical minded, this is known as "one stop" of light. A stop is measured for each doubling or halving of a shutter speed value. Most polarizing filters result in a loss of one to two stops of light.) You may want to consider bringing along a tripod to use in combination with your polarizer, so that you can ensure a steady image if you use a longer shutter speed. (Read more about how to

Maximize your Tripod here.)

A final tip for successfully using a circular polarizer: always rotate the front of the polarizer the same direction you used to screw it on to your lens. When looking at your lens front-end on, the circular polarizer screws on in the clockwise direction. So, when you are rotating the front part of the polarizer to adjust it, I suggest that you keep rotating it in that same clockwise direction. That way you avoid the potential accident of unscrewing the filter by rotating the whole thing instead of just the outer half. Much less likely to lose or drop or break a polarizer that way.

Purchasing a Polarizer

There are two types of circular polarizers available for DSLR cameras. The first type is more traditional and is a single filter you buy that screws on to the front of your lens. You will need to buy a polarizer that fits the dimensions (diameter) of your lens. If you want to use your polarizer on more than one lens, and your lenses have different diameters, then you will need to either buy a different polarizer for each lens or buy a polarizer for the largest lens and then buy step-down adapters to use the larger polarizer on the smaller diameter lens. As an example, my

Tamron 18-270 mm lens has a diameter of 62 mm, so I purchased a

62 mm Hoya circular polarizing filter for it. When I want to then use that filter on my

Canon 18-55 mm kit lens, which has a diameter of 58 mm, I have to also use a

62-to-58 mm step-down adapter to attach the polarizer to the lens. The more lenses you have, the more complicated this can become.

The second type of circular polarizer is sold as part of the

Cokin filter system. With Cokin filters, you buy a

relatively inexpensive filter holder and then

individual adapters that fit the diameters of your lenses, and this holder allows you to use the same filters (including circular polarizers) on all of your lenses. The investment in the filters is often more than buying them individually, but you are not limited in which lenses you can use them with.

Cokin filter systems are also popular with photographers who use multiple filters (such a neutral density or graduate neutral density filters) in addition to a circular polarizer, as the filter holder allows you to more easily use multiple filters at the same time. The larger size of these filters eliminates the vignetting problem common when stacking circular filters.

If you are just starting out with photography and with filters, you may choose to purchase a single circular polarizing filter, which is what I did initially. Well-regarded brands for filters include

Hoya and

B+W. If you are further invested in photography, equipment, and lenses, you may want to consider the

Cokin series of filters and holders. I am seriously considering making the switch myself when I can next justify the expense. Whichever you choose, you will soon find that a circular polarizer is an invaluable tool in helping improve your autumn (and really, all season) photographs.

Want more great ideas? Follow

Boost Your Photography on Pinterest:

Boost Your Photography